We conclude our brief review of colonial buildings in Aguascalientes with a look at a second striking church attributed to a member of the Ureña family of designers and architects.

The Temple of Encino (1773-76)

Located in the ancient city barrio of Encino, construction of the present church started on January 12, 1773. Originally dedicated to St. Michael, in 1796 this church became a shrine to the miracle working Black Christ of Encino, still in place in the apse.

Its extraordinary design has been attributed to Francisco Bruno de Ureña, son of the eminent baroque designer Felipe de Ureña, and some of its features are related to other Francisco Bruno designs such as those for San Diego de Alcalá in the city of Guanajuato and the church of The Assumption in Lagos de Moreno.

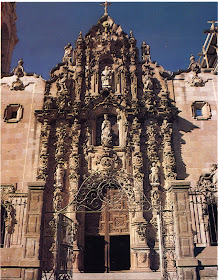

The facade, while still framed in late baroque style, points to later developments, with elements of the neostyle phase of the terminal baroque. Plain, outlying colonettes flank the prominent inner estípite columns, decorated with medallions and lacy rocaille work, while the interestípites are reduced to ornamental corbels supporting the statuary, and vestigial curtain niches overhead.

Sculpted jambs and a scrolled arch frame the rounded doorway, whose projecting keystone supports the overhead medallion with relief of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

In classic felipense style, the columns and pilasters are relegated to the sides of the design, leaving the center façade open for the elaborate openings—the large, decorative doorway with its elaborate relief medallion and the Moorish choir window above.

Sculpted jambs and a scrolled arch frame the rounded doorway, whose projecting keystone supports the overhead medallion with relief of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

In classic felipense style, the columns and pilasters are relegated to the sides of the design, leaving the center façade open for the elaborate openings—the large, decorative doorway with its elaborate relief medallion and the Moorish choir window above.

The upper facade is capped by a simple, rounded pediment, enclosing a sculpted crucifix framed by ornamental rocaille work

The lateral doorway is even more idiosyncratic. Here, an essentially simple format of arched doorway and square pilasters is subverted by irrational, undulating cornices and more rocaille ornament.

In an odd, popular touch, reliefs of a church and a rooster are emblazoned on the pilasters.

The compartmented interior is more conventional, vaulted in white and gold with ornamental ribs and painted oval bosses.

Huge paintings of the Via Crucis (1798) by Andrés López hang along the nave, and a painting of the Baptism of Christ by the noted Mexican artist Juan Correa rests in the baptistry.

Huge paintings of the Via Crucis (1798) by Andrés López hang along the nave, and a painting of the Baptism of Christ by the noted Mexican artist Juan Correa rests in the baptistry.

text © 2013 Richard D. Perry.

Photography by Niccolò Brooker and Enrique Lopez-Tamayo Biosca

look for our forthcoming guide to the work of the Ureña family