The Tlacolula pipe organ

Sunday, February 16, 2014

Oaxaca Historic Organ Festival

Saturday, February 15, 2014

More Hidalgo Missions: Tutotepec

In an earlier group of posts we surveyed the visita churches and chapels of Santos Reyes Metztitlan in the state of Hidalgo, north of Mexico City. We follow this up with a series on some other, less well known early missions of interest in the state, starting with Tutotepec.

San Bartolo Tutotepec

Located in the heart of a traditional Otomí region, the first mission of Tutotepec was also originally dedicated to the Three Kings. It was founded in the 1550s by friars from Atotonilco el Grande, and later became the principal hub for outlying Augustinian visitas in this rugged sierra region of eastern Hidalgo state and parts of adjoining Puebla.

Bird Hill

Although not a dependency of Metztitlan, Tutotepec was evangelized by the pioneering Augustinian missionary Fray Alonso de Borja in the 1530s. Located in the heart of a traditional Otomí region, the first mission of Tutotepec was also originally dedicated to the Three Kings. It was founded in the 1550s by friars from Atotonilco el Grande, and later became the principal hub for outlying Augustinian visitas in this rugged sierra region of eastern Hidalgo state and parts of adjoining Puebla.

Later dedicated to San Bartolo, the present church was built in the 1620s but suffered severe fire damage late in the colonial period and again in the mid 1800s. It has been essentially rebuilt, with a new roof and barn like interior.

Fortunately, its elegant west entry has survived essentially unchanged. The format broadly follows the Renaissance Plateresque style traditionally associated with the Augustinians in Mexico, as derived from their flagship priories of San Miguel Acolman and Metztitlan, although here in a less ornate and more soberly classical version.

The modified triumphal arch design features paired, fluted columns that divide the grand arched entry from the lateral pavilions and frame the intervening sculpture niches. Triangular pediments with dentilled cornices cap the entry and lateral sections.

An abbreviated Latin inscription is emblazoned in Roman capitals on the frieze above the doorway: H(A)EC EST DOMUS D(OMI)NI (This is the House of the Lord)

In classic Augustinian fashion too the facade is replete with relief roundels incorporating religious monograms and the Augustinian insignia, some flanked by flying angels in an archaic style.

Carved stone capitals, possibly from the earlier church fabric or the missing porteria of the adjacent convento, rest in the churchyard.

The lofty nave has been stripped for restoration and the installation of a laminated metal roof.

text © 2013 Richard D. Perry.

color photography courtesy of Niccolò Brooker

We accept no ads. If you enjoy our posts you may support our efforts

by acquiring our guidebooks on colonial Mexico

Tuesday, February 11, 2014

San Caralampio in Mexico

|

| San Caralampio in the cathedral of San Cristóbal de Las Casas |

San Caralampio (St. Charalampos) was an early Christian saint and martyr from the third century AD. A bishop in the central Greek city of Magnesia, like St Denis he was accused by the Roman governor of converting too many pagans, undermining his authority and fomenting a rebellion against Rome—this during a period of religious persecution under the expansionist Emperor Septimius Severus.

Although of advanced age—over 100 by some accounts— Caralampio was stripped of his vestments and brutally tortured. Proving indifferent to his torments, the saint was finally beheaded by order of the exasperated emperor.

Miracles attributed to him before and after his death, included exorcism and healing the sick, especially during the plague, that led to the conversion of many to Christianity including, according to legend, his torturers and even the daughter of the emperor himself!

Devotion to the saint became widespread in the eastern Mediterranean, especially in the Eastern Orthodox church. His cult in the Americas seems to have arisen in central America, mostly in the 19th century, in Nicaragua, Guatemala and later Chiapas in southern Mexico.

|

| The chapel of San Caralampio in Comitán |

Caralampio in Comitán

Comitán is a sizeable town in Chiapas, located on the Pan American Highway between the colonial capital San Cristóbal and the Guatemalan border. A way station on the old Spanish Camino Real, its principal monument is the grand church of Santo Domingo, which faces the large open plaza.

According to tradition, the first image of the saint arrived in Comitán in the 1850s, contained in a traveler's illustrated litany or novena. This document impressed a local admirer in the barrio of La Pila, who erected a simple shrine and chapel dedicated to the saint there.

During a visitation of the plague in the area soon after, barrio residents invoked Caralampio as their protector, with the result that the village was spared its worst effects.

During a visitation of the plague in the area soon after, barrio residents invoked Caralampio as their protector, with the result that the village was spared its worst effects.

Devotion to the saint subsequently spread widely in the area, primarily in the barrios of communities near the Guatemalan border including, besides Comitán, Simojovel and Las Palmas. There is also an image of Caralampio in the San Cristóbal cathedral signifying his wider appeal.

The hillside shrine to Caralampio in Comitán is lavishly ornamented in neoclassical style inside and out. The aged, white bearded saint appears in the center niche of the apse above the altar, kneeling and praying in his traditional pose, with Christ seated above him on a throne in the clouds.

Caralampio is occasionally accompanied by a Roman soldier wielding the executioners sword. Although there is a statue of such a figure in the chapel, it is not always placed in close proximity to the saint.

The festival of San Caralampio in Comitán is celebrated every year coming to a climax on February 11th with special masses and parades through the town that attract visitors and adherents from throughout the region.

text © 2014 Richard D. Perry.

Thanks to Bob and Ginny Guess for their images and information.

All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.

See our earlier posts in this series:

San Antonio Abad, Duns Scotus, San Charbel Maklouf, St Rose of Lima, St Peter Martyr, San Dionisio, St Ursula.

We accept no ads. If you enjoy our posts you may support our efforts

by acquiring our guidebooks on colonial Mexico, including More Maya Missions, our guide to Chiapas

Sunday, February 9, 2014

The Altarpieces of Yucatán: Sotuta

Sotuta

“Swirling Waters”

Sotuta is synonymous with Nachi Cocom, the pugnacious chieftain who spearheaded the Maya resistance to the Spanish conquistadors of Yucatán. In 1546, Nachi Cocom launched a final desperate uprising against the Spaniards and almost succeeded in driving them out. But in the face of terrible casualties, he finally accepted the inevitable and came to an accommodation with the enemy.

Baptized “Juan Cocom,” the Maya leader embraced the Christian faith and became one of Bishop Diego de Landa’s chief informants concerning Maya customs and beliefs.

Although the old Franciscan mission was substantial, it was swallowed up by the enormous 18th century parish church. The imposing west front is framed by multi-staged bell towers resting on broad low bases, and terminates in a broken baroque pediment, with the episcopal coat of arms cupped in its center.

(Note: like Mamá the church front has recently been painted bright yellow, losing its weathered patina)

(Note: like Mamá the church front has recently been painted bright yellow, losing its weathered patina)

The Altarpieces

Although no main altarpiece now remains at Sotuta, several fine old side retablos are preserved in the nave. Now largely restored, they date from 1550 to 1730 and together offer a variety of ornamental treatments within a standardized format common to other colonial altarpieces in Yucatan (at Mani and Sisal).

Standing against the south wall is an attractive pair, transitional in style between Renaissance and baroque. The altarpiece of the Holy Family is the plainer of the two, with decorative plasters. Like most Yucatan retablos, it is predominantly red with gilded scrolled ornament.

Carved reliefs in folkloric style portray Mary’s parents, St. Anne and St. Joachim, and in the pediment above, St. Joseph with a youthful Jesus. A fine statue of St. Joseph occupies the niche (see below)

Beside it is the retablo of the Trinity—similar in color and design but more richly detailed, with twisted Solomonic columns wreathed in vines and outer pilasters with capitals in the form of human heads. Modern statuary occupy the niches instead of reliefs.The retablo of the Sacred Heart (Santa Cruz) features spiral columns throughout with elaborate capitals, and is also painted crimson with intricate floral patterns in gold leaf.

Two statues of exceptional quality stand in the nave. Possibly the remnants from an earlier main retablo, they represent St. Joseph and St. John the Baptist. The latter is the finer work, although in poor condition as of two years ago.

Together they represent outstanding but relatively rare examples of late colonial sculpture in Yucatán.

This is the final post in our series on the altarpieces of Yucatán. Those we have featured are selected from among many other recently restored retablos in the churches there. For other examples see our web site. See our map for the location of the retablos in this series.

text © 2007, 2010 & 2014 Richard D. Perry. Photography by the author

for complete details and suggested itineraries on the colonial monasteries and churches

of Yucatán, consult our classic guidebook.

Friday, February 7, 2014

The Altarpieces of Yucatán: Mamá

Mamá's got a brand new look !

Mamá, a small Yucatecan town of cenotes, well houses and old irrigation channels near Mani, was originally named for a Mayan water goddess, (the suffix -a signifying water.) This ancient tradition was continued in colonial times when the Franciscans dedicated their grand mission church to The Virgin of the Assumption.

The imposing facade is finely ornamented with filigree carving that includes such Marian symbols as the sun, moon, stars and the crown of the Queen of Heaven.

Until recently, the facade was badly cracked and in poor repair. It has now been restored and a coat of orange paint added, which has entailed the loss of its former weathered patina.

Remnants of the colonial water management system still stand, including a large well and channels outside the mission, in addition to a covered noria, or well house beside the atrium, all designed to draw and distribute water from the large cenote underlying the town and mission

The Altarpieces

Over the last decade, conservation measures*

have been under way to restore the altarpieces inside the church at Mamá,

the majority of which date back to the colonial era. The restoration work is now largely complete, transforming

the once dowdy interior into a brilliant display of religious art works and furnishings.

Accented in classic red, white and gold, this triple tier retablo is among the most imposing in Yucatán, although of late date.

The Main Altarpiece

Slender baluster columns. some fluted, some with spirals, frame elegant shell niches, which house statues of Franciscan saints. Floral urns on the later, upper level flank an expansive polychrome relief of St. Francis with the Holy Trinity.

An extraordinary variety of colorful altarpieces in provincial retrobaroque styles are located in lateral niches along the nave. Most feature spiral columns and date from the 1800s.

| El Cordero Painted red, gold and turquoise, it features spiral columns and dates from the 1800s. |

|

| San Antonio Painted red, gold and green, this decorative 19th century retablo is replete with spiraling vines. A mural of the Padre Eterno floats overhead. |

|

| Virgen María A more lightly ornamented retablo features painted baluster columns. Old reliefs of Saints Anne and Joachim flank the central statue of Mary. |

|

| Pasión A classic red and gold altar set in a niche. The Crucified Christ of colonial origin is flanked by medallions of Passion symbols. |

|

One unusual item is this "box retablo" located in the sacristy, designed in the same style as those at Santa Elena. The retablo has painted doors which were closed when viewed; the santo within is unknown although the sun, moon and crown, as seen on the facade, suggest the Virgin Mary.

|

During the conservation process, several mural images were exposed, painted in lunettes above the retablos along the nave. Subsequently restored, they include, among others, a cross, a monstrance, a pierced heart and portrayals of the Lamb of God.

Other restored 18th century furnishings inside the church include the pulpit and a pair of painted wooden lecterns flanking the main altar. There are also newly uncovered colonial murals in the sacristy.

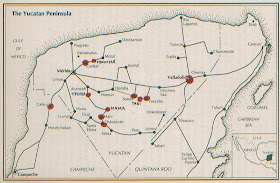

The Altarpieces of Yucatán. MAP

This map is an approximate guide to the locations of the retablos mentioned in our series:

click to enlarge

Wednesday, February 5, 2014

The Altarpieces of Yucatán: Conkal

CONKAL

Place of the Stone Building

Located a mere 18 kilometers from Mérida, San Francisco Conkal was founded in 1549. In 1550 Fray Diego de Landa, then only 26 years of age and at the beginning of his controversial career, became Guardian.Early in the 1600s, Fray Gerónimo de Prat, a prominent Franciscan architect, started work on the permanent stone church. The exterior is severe, its sheer nave walls topped by rows of heavy merlons. The imposing south-facing facade, also plain, with its high, arching pediment and matching rounded belfries, radiates a primeval sculptural strength. The lower facade forms an intricate patchwork of stone mined from the ancient Mayan “stone buildings” in the vicinity.

The simple, pedimented porch is closely related to the doorway of La Mejorada in Mérida, with an arched doorway and flanking pilasters incised with geometrical motifs. Its triangular pediment encloses the Franciscan arms.

Thick interior buttresses between the bays along the nave are pierced by low arches and bold circular openings above, giving the whitewashed interior a cool, sculptural look. The vaulted 16th century open chapel now serves as the sanctuary and houses the large main altarpiece.

A doll like statue of La Purísima with Mayan features appears in the center niche flanked by reliefs of her traditional symbols. Modern paintings of scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary, depicting figures in unusual architectural settings, surround the statue of patron St. Francis in the upper niche.

Elsewhere, God the Father gestures from the surmounting pediment, while portraits of the Doctors of the Church adorn the basal tier, or predella.

The cloister to the rear of the church has been lavishly refurbished to house a Museum of Sacred Art, with a focus on colonial Yucatán.

See our map for the location of the retablos in this series

text © 1988 & 2014 Richard D. Perry

images by the author, Jurgen Putz & Christian Heck

for complete details and suggested itineraries on the colonial monasteries and churches

of Yucatán, consult our classic guidebook.